In May last year, the UK’s Global Underwater Hub (GUH) set a hare running in London with the shocking revelation that 85% of insurance claims associated with offshore wind claims stemmed from power cable failures.

And with the development of offshore wind now storming ahead, projects are about to get more complex and challenging to deliver and manage as floating offshore wind turbines (FOWTs) increasingly take their place alongside the serried ranks of mostly monopile-based structures.

It is because FOWTs are fundamentally different; as tethered floating structures, they move in multiple planes – heave, sway, surge, pitch, roll and yaw.

They are as a result necessarily hooked up to subsea export cables via dynamic riser systems of a type not unfamiliar to many people in the offshore oil and gas industry – from design, to manufacture, to use.

And if offshore windfarm operators are struggling with unacceptable cable failure rates today, which they are, then life is about to get a whole lot tougher for the companies and their insurers if they don’t tackle the problem head-on and harvest the oil and gas experience like never before; notably:

· The subsea expertise that 50 years of offshore oil and gas has honed in centres like Aberdeen, Bergen, offshore West Africa, US Gulf of Mexico and offshore Brazil especially.

· The huge experience of the deepwater drilling industry, much of which is gathered under the IADC (International Association of Drilling Contractors).

In November, the International Marine Contractors Association stated: “According to a report by GCube Insurance in 2021, the average insurance claim nearly doubled from £1.7 million (€2 million) in 2010-2015 to £3.1 million (€3.6 million) in 2020.

“In total, claims for offshore wind grew from around £124 million (€145 million) in 2010-2015 to around £500 million (€585 million) in 2020. Of these, around 50% were down to damage to subsea cables, with other insurers estimating that damaged subsea cables represent between 70% and 80% of their claims.”

Notwithstanding the insurance issue, the future for floating wind is nothing short of incredible. According to DNV’s latest offshore wind analysis, by 2050, up to 300 GW of floating offshore wind (Flow) could be installed globally.

Its most recent Energy Transition Outlook forecasts that 15% of all offshore wind installed capacity will be based on floating projects by then.

“Massive capital is already being injected into the Flow sector, and the first quarter of 2023 recorded some meaningful investment,” records DNV.

“Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners recently announced its intention to invest €8 billion into the 2 GW Nortada Flow project off the coast of Portugal, and EDF recently purchased the Newcastle Offshore Wind project, a Flow project in Australia with a potential capacity of up to 10 GW.”

All told, the UK’s ORE Catapult estimates that 54 countries pass the initial technical and socio-economic thresholds evaluated for Flow development. It estimates that “these identified markets have a combined technical resource potential exceeding 32,000 GW” already.

This should be manna to the UK and Norway especially as the North West Europe Continental Shelf is global leader for offshore wind with more seafloor-fixed turbines planted out than anywhere else in the world; and the largest expressed ambition to date for FOWT-based projects.

Europe has demonstrators like Hywind Scotland and the Kincardine project in UK waters and Hywind Tampen (Norwegian sector) showing the way forward for oilfield electrification. However, the Portuguese were first with the WindFloat Atlantic development brought onstream in 2019.

Here in the UK, the still oil & gas dominated subsea sector, all key supply chain elements of which are mostly wholly or in part foreign-owned and/or financed, has been slow to grasp the offshore wind nettle.

However, GUH’s CEO, Neil Gordon sees a second bite at the cherry in the shape of floating wind; moreover a far bigger bite than anything so far associated with fixed turbines.

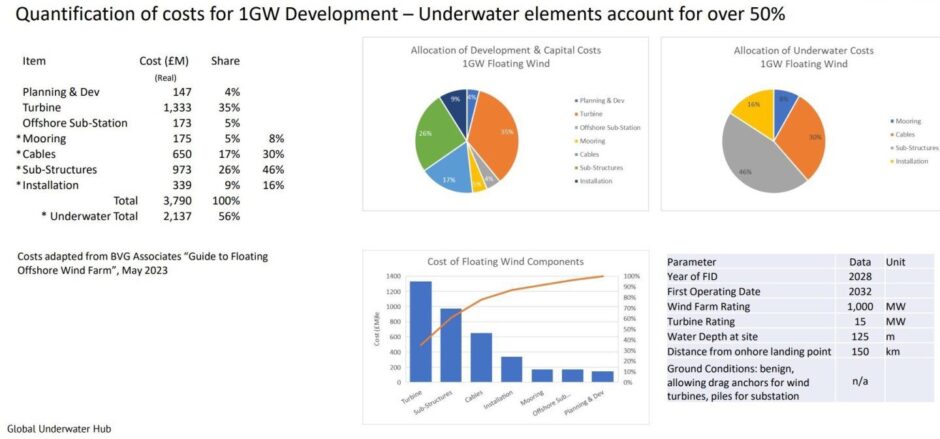

Moreover, the scale of the opportunity was set out at the London session in research carried out by GUH with some costs adapted from BVG Associates “Guide to Floating Offshore Wind Farms”, May 2023.

The headline result of GUH’s number crunching based on a 1,000 MW (1 GW) project is that more than half of the cost of a floater-based windfarm is subsea, 56% to be exact.

That represents a massive prize to go for. Far more proportionately than the subsea element of fixed turbine projects.

This part of the North Sea Energy Transition should be a no-brainer for Aberdeen with its still strong, capable and international subsea sector; project engineering and management; a relatively modern and versatile fleet of ships; specialist engineering-manufacturing; and a proven R&D track record.

However, the race is already on with other centres, notably Bergen/Stavanger in Norway which, together, have enjoyed a clear head-start over the UK. This is thanks to Hywind, a willing offshore industry, excellent research funding and committed semi-state energy companies, namely Equinor. Under its original name Statoil, Equinor inherited the Hywind and sister Sway floating turbine IP when it took control of Norwegian competitor Hydro in 2007.

GUH’s Neil Gordon is seriously excited by the Flow possibilities.

“By considering feedback gleaned from the (London) workshop element of the event, the Global Underwater Hub has identified a number of areas which can be focused on and are applicable across the full life cycle of subsea cables, including design, manufacturing, handling & installation, operations & maintenance and insurance risk,” he says.

“These broadly take the form of a quadrant model focusing on areas of knowledge and data sharing, industry standards & specification, innovation & technology and skills & training. This quadrant lens can be applied across each area of the life cycle as well as identifying common themes (golden threads) and inter-relationships amongst areas (i.e. manufacturing into installation).”

Another result of the London session is that a Subsea Cable Industry Forum has been convened to focus on areas of opportunity, improvement and cross functional learning across the life cycle functions of subsea cables to improve reliability, longevity and reduce failures.

The industry needs to be looking at the integrated solution. This is where some aspect of control around guidelines on standards and specifications allows industry to collaborate, work to a set of agreed standards or guidelines, build to a standard of quality and at scale without re-engineering each project.

It perhaps helps the likes of Aberdeen that offshore wind developer BlueFloat Energy thinks of fixed base and Flow as two “parallel industries”, noting that the “development strategy [for Flow] requires a very different approach and mindset”.

Of course, the fundamental technological difference is the turbine format itself – fixed foundation versus floating and tethered.

The choice of floating foundation will depend on the location of the project, seabed conditions, predicted wind speeds and turbine size.

At present, there are more than 50 different Flow concepts under development, including research into how Big Oil itself went about tackling related challenges when developing floating production systems: semi-submersible, spar and ship-shaped.

There is and has been a lot of research going on in the area of dynamic cables, but apparently not in a truly co-ordinated way. One of the key issues is that there is lots of different research going on is small pockets which is not joined up, something the forum hopes to fix.

There is a role for government, London and Holyrood in all of this, but the opportunity has to be treated seriously and in a sustained manner.

Tim Pick, the UK’s offshore wind champion appointed in 2022 at the same time as a £160 million Flow support fund was announced by Westminster, believes this is an area for care and attention by government, notably:

· Supporting innovation to achieve the commercialisation of Flow;

· Taking a sustainable approach to the CfD (Contracts for Difference) auction process – which has taken a beating as a result of the recent offshore wind licensing round total failure.

· Accelerating investment in port infrastructure.

Whilst it is expected that the main roll-out of UK Flow will take place during the 2030s, the 2020s will play an important role in realising the necessary pre-emptive cost reductions required to capture industrial benefits and early mover advantages.

Up to 15GW of installed capacity could be operational by 2030 if new markets open up and countries create the necessary regulatory frameworks and supply chains to achieve commercialisation.

Whether Pick or the £160million wind floater fund survive the General Election and probable ousting of the Tories at the end of this year is of course open to question.

However, given the massive future potential role for the subsea industry let alone ports and harbours and fabrication facilities in this subsea of offshore wind, the next government will need to be very canny about.

© Supplied by GUH

© Supplied by GUH © Supplied by All-Energy

© Supplied by All-Energy