© Supplied by TenneT

© Supplied by TenneT While energy production is at the forefront of many energy transition discussions, moving that energy around is equally important.

That is especially true for electricity transmission system operator (TSO) TenneT, which manages national and cross-border grid connections across Germany and the Netherlands.

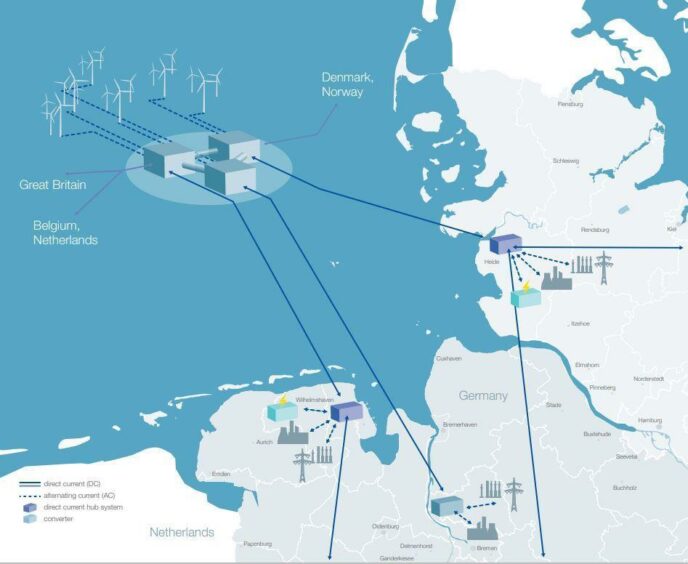

Increasingly, its work includes the creation and management of offshore transmission hubs for wind projects. In addition, new developments will see larger capacity substations capable not only of connecting wind farms to shore, but linking wider electricity markets to enable cross-border trading.

An initial program envisioned the creation of artificial “Power Link” islands in the North Sea, enabling interconnectors, hydrogen production and offshore wind maintenance bases all at once site, though more recently attention has focused on a smaller, more diverse “hub and spoke” model.

In 2020, TenneT and National Grid Ventures, the commercial development arm of the UK’s National Grid, announced a cooperation agreement to explore the feasibility of connecting Dutch and British wind farms to the energy systems of both countries.

A first-of-its-kind project for both markets, the so-called multi-purpose interconnector (MPI) would simultaneously connect up to 4 gigawatts (GW) of British and Dutch offshore wind, and would provide an additional 2GW of interconnection capacity between the countries.

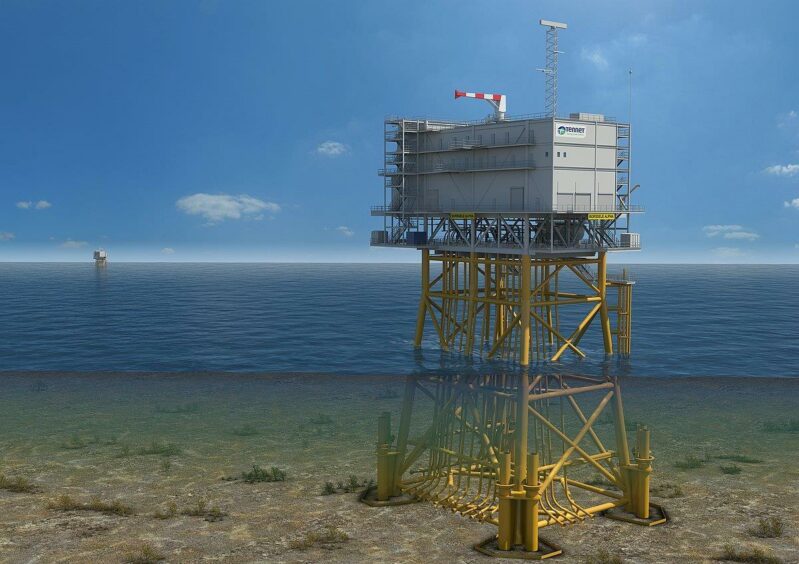

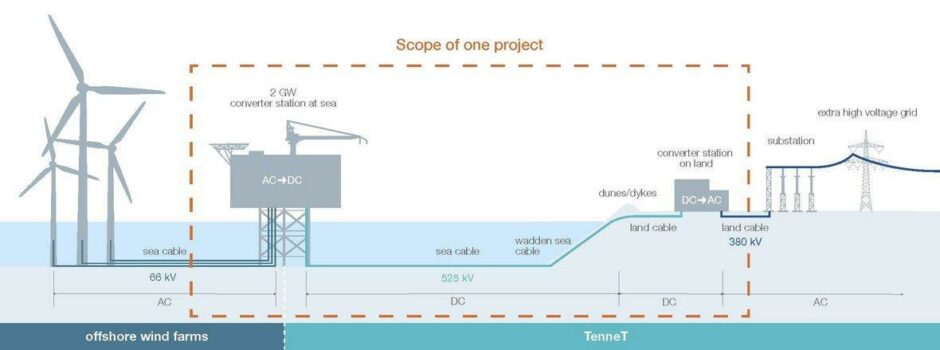

Indeed, TenneT’s wider goal is to see this become a standard for offshore transmission, as part what it calls the “2GW Program”. This would see the adoption of a new standardised substation platform and a new certified cable system – both developed with TenneT’s oversight – enabling higher transmission capacity with a lower environmental footprint.

TenneT advisor for offshore development, Timo Kahl, explains: “The size of offshore connection systems is mostly between 700 MW in The Netherlands and 900 MW in Germany currently.”

“Moving to a 2GW standard decreases the effort for the same amount of electricity – that means you need, per kWh, less material, less cost, less environmental space and so you get significant increases in efficiency.”

Mr Kahl adds that while the transmission platforms will be slightly larger than the models used currently, only one will be needed where two were required previously – and the same for the cables that take power to shore.

TenneT will build at least six offshore grid connections in this manner in Germany and the Netherlands by 2030, three in each country and enough to support 20% and almost 30% of each nation’s respective offshore energy goals.

The TSO has already launched the tendering procedures for the onshore and offshore stations for the German projects, BalWin 1,2 and 3. Contracts for all three projects have a combined order volume “in the seven-digit range” and are expected to be awarded in the third quarter of 2023.

While the economies of scale and efficiency are promising, there remain some challenges to overcome. One issue, which has become apparent during the National Grid project, lies in the operation of offshore wind farms themselves.

Some wind farm operators have warned of a lack of clear regulatory framework, especially concerning how they would operate a wind farm linked to an interconnector that connects two countries, and have called for these “hybrid” projects to form a new distinct asset category to distinguish them from interconnectors.

This is partly due to European regulation, where the so-called “70% rule” included as part of the EU Clean Energy Package, means that TSOs are required to guarantee that at least 70% of transmission capacity is offered for cross-zonal trade, while respecting operational security limits.

Timm Krägenow from the Brussels office of TenneT says it has left some offshore wind farm operators asking for clarity around their business model, though the industry remains supportive of the development of these hybrid projects or MPIs.

TenneT is confident these can be overcome. “There would be different ways how to provide such a business case and we as TenneT are saying it’s an important opportunity to build such MPIs,” adds Mr Krägenow.

He also makes the case for future-proofing those substations being installed today, to allow them to potentially be integrated or retrofitted with interconnection technology at a later date, something he says TenneT is also making the case for.

While offshore wind connections progress, other energy integration projects, such as hydrogen production for example, are likely to remain onshore, at least for now.

Adds Mr Kahl: “There might be some areas where offshore hydrogen production makes sense, even in combination with our offshore electricity grid, but currently the focus of the German government is to reach the 70 GW [offshore wind target] and then shift the hydrogen protection more to the shore.”

Nevertheless, momentum is growing. Alongside the UK, Danish authorities have also signed memorandum of understanding which would see even greater integration between its northern European neighbours.

With TenneT’s technology and the driving force of ambitious offshore wind targets across the North Sea, the vision of the SNS as a wind hub of the future is beginning to take shape.