Tens of thousands of jobs in Scotland are reliant on the UK achieving a successful transition to cleaner energy, a new report has found.

If Scotland is successful in delivering on its energy transition ambitions, the offshore energy workforce could increase by an estimated 25%, from 79,000 roles to close to 100,000, the report from Aberdeen’s Robert Gordon University (RGU) has found.

However, failure to capture the full range of offshore energy and UK content opportunities could see Scotland’s offshore workforce fall by around 48% to 48,000 roles by the end of the decade.

Avoiding this will require faster progress on ScotWind and Innovation and Targeted Oil and Gas (INTOG) leases, as well as new hydrogen and carbon capture and storage (CCUS) projects, including the Scottish Cluster, according to the report.

It also requires maintaining activity in the oil and gas sector.

The 52,000 job difference

The UK will fail to achieve a “just and fair” transition to clean energy by 2030 without urgent action, the report warned.

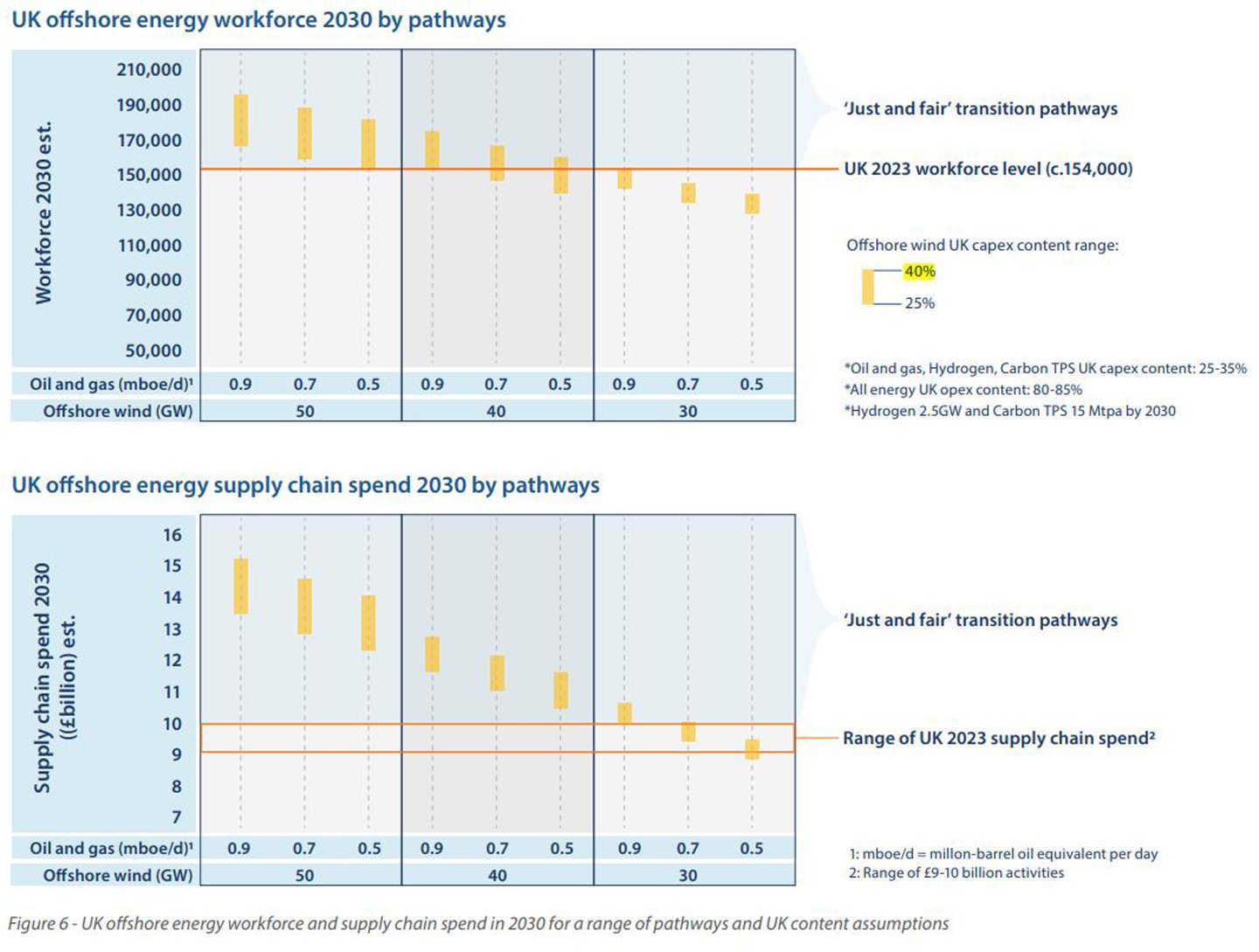

The RGU ‘Delivering our energy future‘ report analysed over 6,500 different pathways for the UK offshore energy industry between now and 2030.

However, fewer than 15 (less than 0.3%) of the routes analysed met the principles for the just and fair transition it calls for.

Among its key findings, the report concluded that UK and Scottish political decisions, rather than energy market economics, will determine the future size of the UK energy workforce and supply chain.

The report also highlighted the disproportional impact to supply chain jobs in Scotland without intervention, particularly in the North East.

The researchers argue the 154,000 jobs currently directly or indirectly supported by the offshore energy sector across the UK will need to be maintained or increased to meet its criteria for justness and fairness.

RGU estimates the offshore energy sector needs to invest £200 billion over the remainder of this decade across offshore wind, hydrogen, CCS and oil and gas projects.

This also means the industry will have to achieve close to 40GW offshore wind capacity by 2030, increasing UK content in the offshore wind supply chain to 40%.

‘Unique opportunity’ for UK energy future

RGU Energy Transition Institute director Professor Paul de Leeuw said despite the limited pathways available, the UK still has a “unique opportunity to create a new energy future”.

“Accelerating the re-purposing of the North Sea as a world-class, multi-energy basin will ensure the sector can power the country for decades to come,” he said.

“But to deliver this requires action and urgency, which means faster planning and consenting and access to the grid.”

Professor de Leeuw said the UK will also need more flexible electricity pricing mechanisms to avoid project delays as well as a “proactive focus” on building the UK supply chain’s ability to deliver critical new energy infrastructure.

“This, as well as building and maintaining the world class skills and capabilities developed over the last few decades, will be crucial,” he said.

While there is broad consensus on the need for a just transition for the offshore oil and gas workforce, Professor de Leeuw said achieving it will require a “far more agile and joined-up approach”.

“The latest research reinforces the need for urgent alignment across the political spectrum to agree the short-term actions that will deliver a just and fair transition, maintaining the workforce to 2030 to deliver a long-term net zero future and the associated economic benefits for the country,” he said.

Delivering 40GW offshore wind will be key

According to the report, the ongoing decline in the North oil and gas industry needs to be offset much more rapidly by identifiably greater levels of activity and higher UK content in renewables if any of the pathways to a “just and fair” transition are to remain open.

If the UK cannot deliver close to 40GW of offshore wind capacity by 2030, up from the 15GW currently installed, it is unlikely the offshore energy workforce will be retained without additional activities, Professor de Leeuw said.

Otherwise, interim steps will need to be taken to address the decline in activities, including oil and gas production – which is currently expected to reduce by more than 40% by 2030.

“To achieve this outcome, the UK offshore energy sector needs to deliver on spend of up to £200 billion over the remainder of this decade across offshore wind, hydrogen, carbon capture and storage (CCS) and oil and gas projects,” Professor de Leeuw said.

“Given the magnitude of change that is needed in the energy industry over the coming years, this report is highlighting that the UK, and devolved administrations must urgently pursue credible energy pathways, which deliver a ‘just and fair’ transition for the sector and its workforce.”

Last year, a report by trade body Offshore Energies UK (OEUK) highlighted that ongoing political uncertainty is holding up around £100 billion worth of North Sea projects.

UK and Scottish political decisions

Ongoing political and fiscal uncertainty has dented investor confidence in the UK oil and gas industry, with “negative implications for energy sectors”, the report states.

Accelerating the rollout of renewables by streamlining planning and consenting, providing targeted support and implementing “appropriate fiscal mechanisms” will be “critical”.

Professor de Leeuw pointed to the slow progress of the 4.1GW Berwick Bank offshore wind farm, which is still awaiting approval from Scottish ministers.

Last year, renewables advocates also warned that a two-year delay to the Scottish Government’s energy strategy is putting billions of pounds of investment at risk.

North East Scotland disproportionately affected

The RGU report highlighted the disproportionate impact failing to achieve a just transition will have on the North East of Scotland.

The UK offshore energy sector employs or supports approximately around one in 220 of the working population in the UK, compared to one in 30 in Scotland.

In the North East of Scotland, the figure is even more stark, with one in five working age people directly or indirectly employed in the energy sector.

The offshore energy workforce in Scotland is also more heavily dependant on oil and gas than the rest of the UK.

Nearly 87% of Scottish offshore energy roles are in oil and gas, compared to 67% in England and 78% across the whole of the UK.

Increasing UK supply chain content

Increasing the amount of work UK and Scottish supply chain firms contribute to energy projects – often referred to as local content – will also be key to ensuring a ‘just and fair’ transition.

Under the UK government’s 2020 offshore wind sector deal, industry committed to increase UK content to 60% by 2030.

Meanwhile, bidders in the ScotWind process were required to submit a supply chain development statement (SCDS) detailing how they would use Scottish industry.

RGU estimates that each additional 10% in UK capex content for the offshore wind sector could add between 3,000 and 12,500 jobs by 2030.

Delivering up to 40% capex content for new offshore wind projects and up to 50% for oil and gas decommissioning activities by 2030 will require developing significant amount of new capacity and capability” across the UK.

But the shift in the offshore energy workforce from operational activities to capex activities will also have an impact on the sector’s economic contribution.

Building renewables projects will see the UK energy industry shift towards a greater share of technical and vocational occupations, which tend to pay lower salaries than in professional occupations such as engineering.

Salaries in the renewables sector also tend to be lower than in the oil and gas sector.

As a result, the report found the offshore energy sector may require a larger workforce to provide the same level of economic contribution as it does now.

For every 10% difference in salary, the RGU analysis showed the number of jobs will need to increase by 7%.

This means that by 2030, the offshore energy workforce will need to increase to 165,000 role to sustain the same overall economic contribution as the 154,000 currently employed.

UK needs ‘clear pathways’

Professor de Leeuw said the UK and Scottish governments need to formulate a credible strategy to achieving a just and fair transition.

“I think as a country, we’re not short on ambition,” he said.

“What we really need is the clear pathways to get there, and what we have done in this report is to inform these pathways.

“You have to start doing.”

Recommended for you

© Supplied by Ocean Winds

© Supplied by Ocean Winds © Image: Big Partnership

© Image: Big Partnership © Image: Robert Gordon University

© Image: Robert Gordon University © Supplied by Forth Ports

© Supplied by Forth Ports © Wullie Marr/ DCT

© Wullie Marr/ DCT © Supplied by DCT / Sandy McCook

© Supplied by DCT / Sandy McCook