As a host of challenges frustrate the UK’s ambitions for floating offshore wind projects, could a different kind of turbine get the industry back on track?

The UK remains a world leader in floating offshore wind (FLOW), with around 80 MW in installed capacity and a 35GW pipeline of projects, including 29GW in Scotland.

But recent analysis of the UK floating wind sector forecast just 500MW in installed floating wind capacity by the start of 2030, falling far short of the UK government’s target to have 5GW by then.

It comes as just 4% of industry leaders think the UK will meet its wider 2030 offshore wind target, with supply chain shortages, ports and grid access highlighted as key barriers to progress.

But Swedish firm SeaTwirl believes it has a solution for some of the cost issues affecting floating wind – vertical axis wind turbines (VAWTs).

SeaTwirl vertical axis wind turbines

SeaTwirl chief executive officer Johan Sandberg told Energy Voice that prior to taking on the role, he became concerned about the challenges facing the sector.

Mr Sandberg began his career in floating wind with DNV in 2008, and also worked across ScotWind bids with Aker Offshore Wind (now Mainstream Renewable Power).

But while attending an offshore wind conference in Aberdeen in 2022, Mr Sandberg said he began to feel the industry needed a new approach.

“It just dawned that after 15 years, I really couldn’t see us as an industry achieving the cost reductions that we need to do in floating offshore wind,” he said.

“I could see the high interest rates, the high commodity prices, the bottlenecks in the supply chain, all of that would hit the offshore wind and it would really delay all of our projects.”

These fears were well founded, with the offshore wind industry experiencing something of a crisis in 2023, particularly in the UK.

Mr Sandberg said the floating wind industry is also struggling, with delays to projects in Scotland and Norway.

“So as an industry, we need to think out-of-the-box,” he said.

VAWT benefits

Mr Sandberg said while SeaTwirl’s vertical turbines are not the solution for every offshore wind project, they do offer many benefits, including easier, cheaper maintenance particularly for smaller projects.

Currently, floating turbines at the Kincardine and HyWind Scotland projects are being towed to the Netherlands and Norway respectively for maintenance campaigns.

This makes it a difficult sell for turbine suppliers when coming up with maintenance strategies for larger scale projects, Mr Sandberg said.

“We don’t have anything to lose by really exploring something new, something different,” he said.

While SeaTwirl is certainly proposing something different, it is not a newcomer to the floating wind sector.

The Gothenberg-based company installed its first prototype in the water off the coast of Lysekil in Sweden in 2015.

The 30kW S1 turbine has been in the water, connected to the grid and operating continuously ever since.

“It’s never been taken out of the water, they’ve always done the maintenance on site without any cranes,” Mr Sandberg said.

SeaTwirl’s goal is not to compete with major European wind turbine developers like Vestas or Siemens, Mr Sandberg added.

“Our purpose is to enable floating wind power wherever it is needed,” he said.

“If a ScotWind developer wants to use us for a ScotWind site, we’re more than happy to supply turbines for that.

“But our main focus now is to actually electrify oil and gas or any project which is less than 100MW.”

Offshore electrification

Mr Sandberg said larger offshore wind turbine developers, such as Vestas and GE, do not have the resources to supply projects smaller than around 750MW.

As a result, he said SeaTwirl sees an opportunity to provide a technology solution for smaller offshore electrification projects.

Apart from offshore oil and gas, Mr Sandberg said other offshore applications include fish farms, military installations, and remote island locations.

Maintenance costs

SeaTwirl’s design extends the tower down through the generator house and becomes a spar, with the rest of the structure rotating in the wind.

“There’s no moving components in there at all,” Mr Sandberg said.

“There is no pitch system, so everything that can break is now condensed into the generator house.”

Having access to the generator, gearboxes and bearings at sea level, rather than up to 200 metres in the air, makes the maintenance process much easier, he said.

SeaTwirl also focuses on using smaller components which are easier to replace, with multiple smaller generators in each turbine rather than one large one.

Spare components can be stored offshore in each turbine, allowing for easier replacement during shorter weather windows in the winter.

The lower centre of gravity also leads to less bending movement in the structure, requiring less steel for construction and reducing costs.

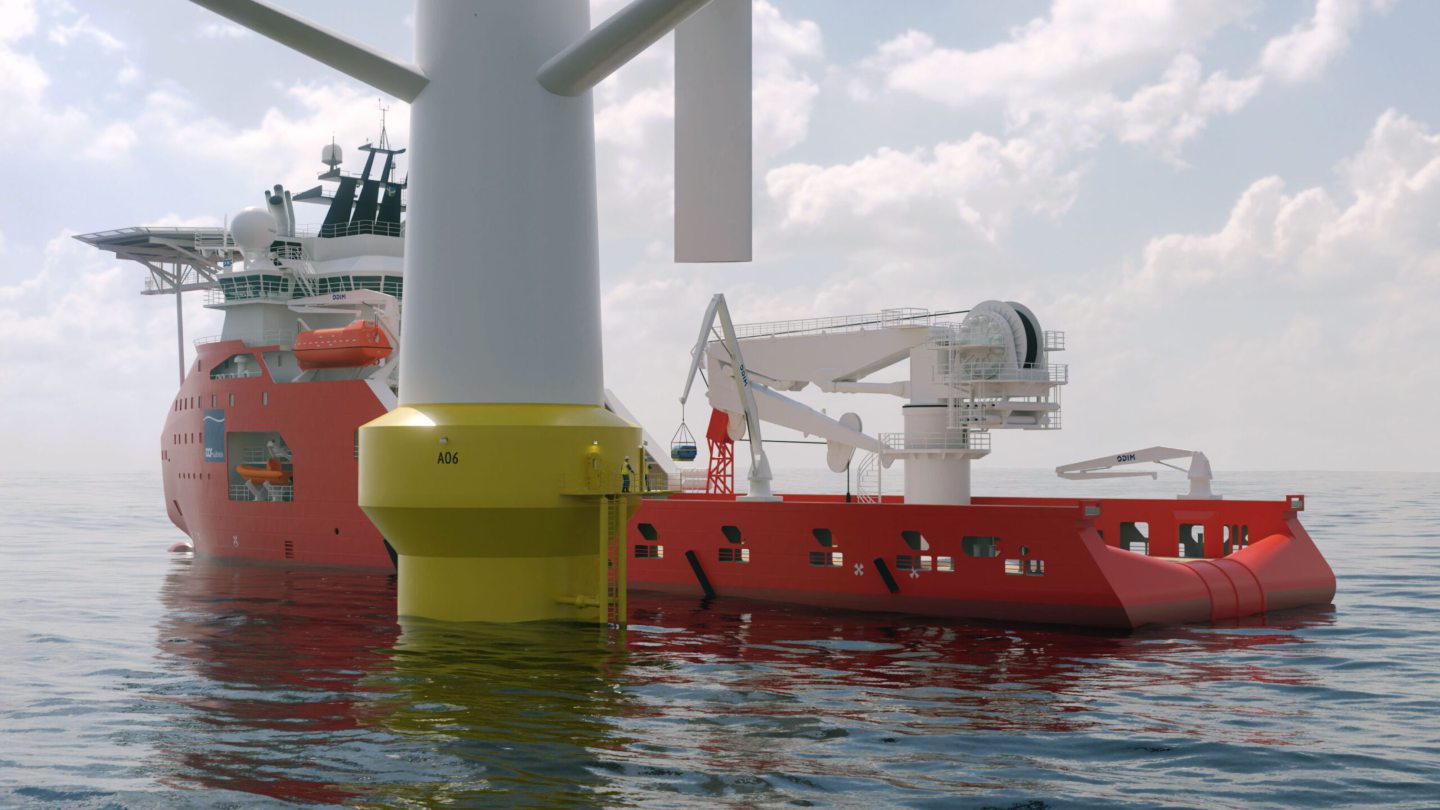

Other advantages include a lower rotational speed, leading to reduced blade erosion and potentially fewer seabird collisions, the ability to use smaller and cheaper installation vessels, and simpler manufacturing processes compared to conventional turbines, Mr Sandberg said.

North Sea electrification

Looking ahead, SeaTwirl is focusing on providing its smaller S1.5 model for electrifying offshore and subsea equipment in the 200kw to 400kw range.

Mr Sandberg said there is a “huge” potential market for turbines in the offshore oil and gas sector, particularly for smaller projects involving five to 10 turbines.

As part of that approach, earlier this year SeaTwirl signed a memorandum of understanding with subsea power solutions firm Verlume to explore opportunities for collaboration on offshore electrification and decarbonisation.

Fresh from offshore trials with wave energy firm Mocean Energy, Verlume chief executive officer Richard Knox told Energy Voice the firm is keen to explore opportunities for similar subsea electrification projects with SeaTwirl.

North Sea operators Shell, TotalEnergies, Serica Energy and Harbour Energy were all partners in the RSP project, alongside Baker Hughes and Thai national oil company PTTEP.

SeaTwirl and INTOG?

TotalEnergies and Harbour Energy are also developing small floating wind projects focused on decarbonising offshore oil and gas assets as part of the INTOG round.

Mr Sandberg said SeaTwirl is speaking to INTOG developers, as well as the Net Zero Technology Centre and the North Sea Transition Authority, about incorporating its turbines for electrification projects offshore.

However, he said he could not confirm which INTOG developers SeaTwirl is speaking to due to confidentiality.

In July last year, SeaTwirl announced its first commercial revenues from through a purchase order for an S1.5 turbine for a North Sea project in collaboration with Norway’s Havram.

Mr Sandberg SeaTwirl is also exploring opportunities in Japan with Sumitomo and in Brazil and the Gulf of Mexico with Oceaneering.

Other dialogues are ongoing with operators in the Middle East and Southeast Asia, he added.

Scaling up

Elsewhere, SeaTwirl is progressing plans to build and test its larger 1MW S2x turbine.

A protype S2x turbine is currently under construction in Sweden, with plans to install it for testing at the METCentre in Norway in 2026.

However, alongside the rising cost of capital, Mr Sandberg said a major challenge for SeaTwirl is the “conservative” nature of the offshore energy industry.

“Everybody knows that vertical wind turbines couldn’t compete onshore, so why would they now compete offshore?” he said.

“But what they seem to forget is that FLOW is very different from bottom-fixed.

“We are not saying that vertical towers would ever compete in the bottom-fixed setting, but for floating the conventional technology has so many different challenges compared to bottom-fixed that the vertical turbine suddenly comes up very differently in that context.”

VAWT research

SeaTwirl isn’t the only company to see the potential benefits of vertical axis turbines for FLOW installations.

The US Department of Energy recently completed a VAWT project, while the Japanese government is also funding a VAWT demonstration project.

Meanwhile the European Union is seeking research and development partners for a VAWT trial with an undisclosed firm in the UK.

But although many VAWT developers like Norway’s World Wide Wind are continuing to invest in scaling up their technology, over the years many other developers have fallen by the wayside and scepticism remains.

If SeaTwirl can successfully deploy its turbines in the harsh North Sea environment, it should go a long way towards proving the potential for VAWTs.

Recommended for you

© Image: SeaTwirl

© Image: SeaTwirl © Supplied by SeaTwirl

© Supplied by SeaTwirl © Supplied by SeaTwirl

© Supplied by SeaTwirl © Supplied by SeaTwirl

© Supplied by SeaTwirl © Supplied by SeaTwirl

© Supplied by SeaTwirl © Supplied by SeaTwirl

© Supplied by SeaTwirl © Supplied by SeaTwirl

© Supplied by SeaTwirl