The UK is preparing to pull back its target of building 55 gigawatts of offshore wind capacity by the end of the decade.

The government may step back from the goal after early analysis showed that the nation will probably need less offshore wind than Labour was expecting, according to people familiar with the matter who asked not to be identified because discussions are private. The target was slightly bigger than the previous government’s already ambitious goal of 50 gigawatts.

It’s not clear that Britain needs that much extra electricity. Demand is expected to increase sharply by 2050 but the rise is more modest by 2030. Even if there were developers willing to build the capacity, supplies of turbines, cranes and ships are already strained. Without proper preparation of the country’s network, the grid could be flooded with power meaning the farms need to be switched off at times.

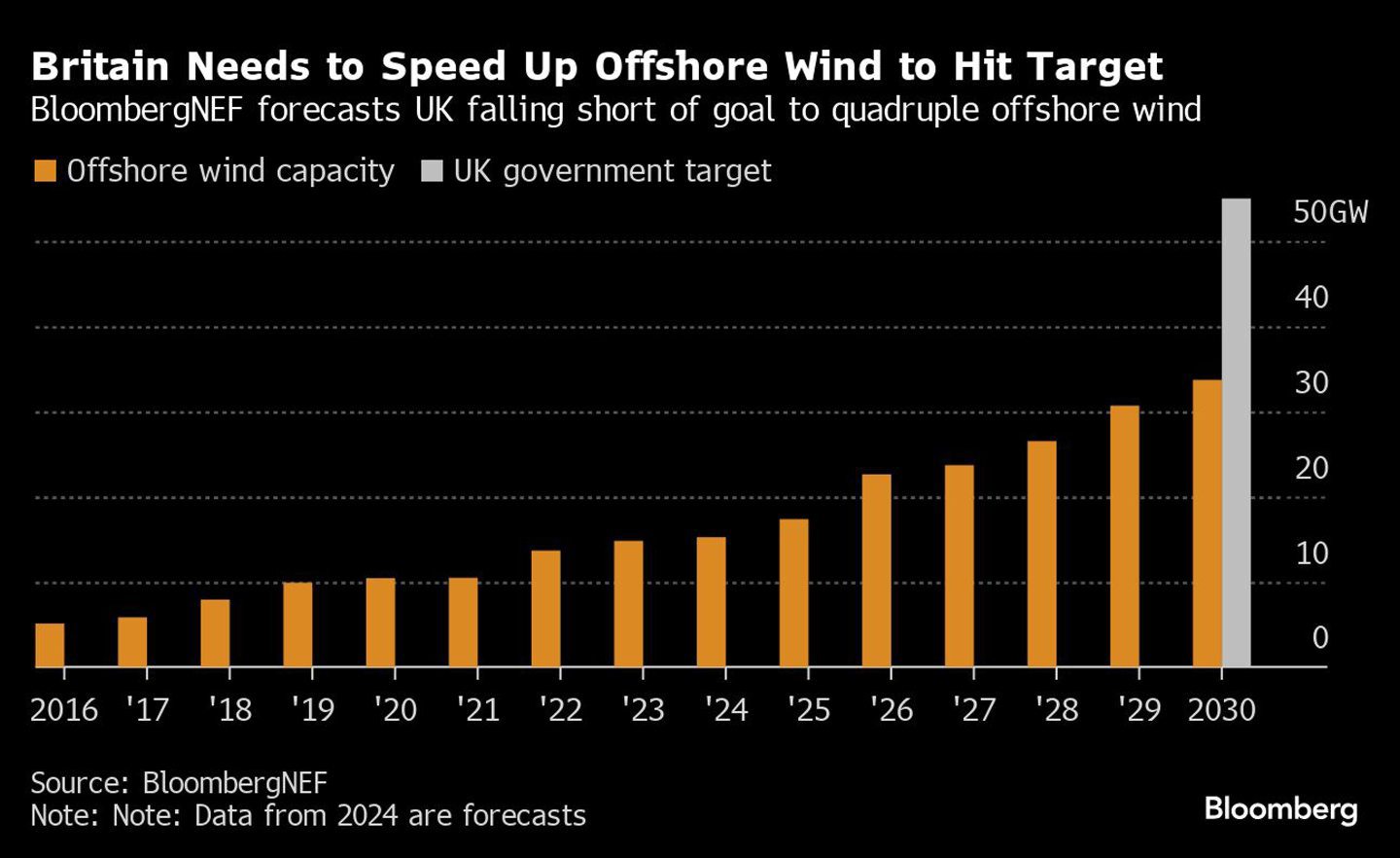

Analysis published earlier this year by the the Climate Change Committee, the body that advises the government on climate policy found that Britain wasn’t on track to reach 50 gigawatts in 2030. Showing that the country can still meet its goals with less offshore wind could be a helpful way for the government to back out of a target it’s going to miss anyway.

That moment could come later this year when the government fleshes out how it will achieve a zero-carbon electricity grid by the end of the decade. Chris Stark, former head of the nation’s independent Climate Change Committee, is spearheading those efforts and is poised to publish a set of recommendations following a call for input from the country’s grid operator. The change in the offshore target may come as a result of that detailed work, said one of the people.

Asked whether 55 gigawatts was necessary, Stark said he’s more focused on the whole system rather than any specific number.

“Reaching the 2030 goal of clean power is more important than getting to those exact targets,” he said on the sidelines of a conference in London this week.

Scenarios that the country’s grid operator will deliver to the government will likely have different options for the amount of wind power needed, he said.

Britain has scaled up its offshore wind fleet in recent years to about 15 gigawatts, the most of any country other than China. In 2020, then Prime Minister Boris Johnson set a 40 gigawatt target in a bid to revive the economy after Covid-19. Less than two years later, Johnson increased the 2030 goal to 50 gigawatts following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. That was topped by Ed Miliband, now the energy secretary, with 55 gigawatts. Labour also vowed to add 5 gigawatts of floating offshore wind.

“We are committed to making Britain a clean energy superpower by 2030 by doubling onshore wind, tripling solar power and quadrupling offshore wind,” a spokesperson for the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero said in an emailed comment to Bloomberg News.

Peak demand is below 65 gigawatts in 2030 in all four scenarios modeled by the Electricity System Operator, compared to 58 gigawatts now. It will jump above 100 gigawatts in all cases by the middle of the century.

The UK runs an auction to secure its electricity generation mix five years in advance. Now, wind makes up about 30% of total generation but it needs to be underpinned by stable generation like nuclear and gas. The latest process procured 43 gigawatts of capacity, 67% of which was gas plants. It’s unlikely that this would be totally upended by the end of the decade.

“That is just much more wind generation than the system can absorb,” said Tom Smout, an analyst at Aurora. “There isn’t demand for that much generation, so you would end up having to curtail a lot of that wind power.”

© Supplied by Bloomberg

© Supplied by Bloomberg