2022 saw a great deal of turmoil in energy markets, to be sure, but it also heralded some landmark moments for the future of renewable energy.

Perhaps chief amongst these was Scotland’s long-awaited flagship offshore wind auction, ScotWind, which brightened early January with news of an historic procurement of new fixed and floating offshore wind power.

Overseen by Crown Estate Scotland (CES) for the first time, the leasing round saw 17 projects offered option agreements, from a total of 74 applications. Coupled with a further three projects from the year’s subsequent “clearing” round, more than 27.5GW of new wind capacity is now on planning sheets for delivery beginning in the latter part of the decade.

Amongst success for developers, the round raised around £750 million in option fees to be paid to the Scottish Government for public spending.

Little wonder then that outgoing CES chief executive Simon Hodge called the announcement “arguably the most significant moment in Crown Estate Scotland’s five years of existence” in a parting statement within the organisation’s annual report.

Yet, as CES’ head of offshore wind development Colin MacIver makes clear: “The outcome of ScotWind isn’t the end of the story.”

While he and his team were pleased to see 20 “very credible, very capable project developers” get through the to the development phase, plenty more work remains in place to deliver on the round’s ambitions. “We didn’t pause too much for celebration – although it’s an important milestone it’s really just the end of the beginning.”

Nevertheless, the signals sent by the round and the appetite of the energy sector are cause for optimism. “It shows the market in the UK and Scotland in particular, is very buoyant and there’s been significant demand for the development rights, and I think that’s really encouraging for the work we’re doing and the opportunities that can come from the offshore wind sector,” he continues.

The process has been no small undertaking for an organisation created just five years ago via the devolution oversight by the UK’s Crown Estate, which has historically managed the offshore leasing process.

Mr Maciver said overseeing ScotWind was a new process for the team, with “quite specific long-term objectives” that included both its management of the seabed, but also ensuring the development of successful offshore wind sector, creating economic value for Scotland and supporting a wider just transition for the North Sea.

The year since last January’s announcement has seen the groundwork for this mammoth build-out begin to be scoped out. Maciver points to project teams becoming embedded, and developers beginning to establish project identities.

That includes CES’ own plans to double the size of its energy and infrastructure team to help deliver the country’s net zero commitment, and the recruitment of new chief executive Ronan O’Hara to succeed Mr Hodge following his retirement.

“Now we’re starting to see where people can make early progress and where some of the key opportunities are to overcome issues and where some solutions lie.”

“We had a big reaction to the scale of project ambition in terms of capacity,” he adds. “For the core issues in terms of development phase – consents, supply chain and grid – I think we’ve seen a proportionate reaction from National Grid, the transmission companies, Marine Scotland – all recognising the scale and nature of the opportunity.”

“Now we’re working to build a supply chain that’s capable of delivering for Scottish projects which can ultimately get them built, operational, safe and delivering the sort of value that that we’re looking for from the sector.”

Supply chain

Fostering a local supply chain was also central to the process, with ScotWind bidders required submit a Supply Chain Development Statement (SCDS) setting out anticipated levels of local content from each phase of their proposed projects.

Spending commitments averaged just shy of £1.4bn per project, putting Scotland in line to benefit from more than £28bn in local investment. The hope is that these plans go some way towards correcting a trend that has seen previous offshore wind buildouts largely pass local firms by.

And while local content requirements are nothing new, the SCDS approach is aimed at providing value beyond quotas. “The value from SCDS is in information. It’s in visibility and consistency of information in the first place,” Mr Maciver says.

Developers must update these SCDS within 12 months of signing their agreements – Mr Maciver says an update is due in the first quarter of 2023 – and at least every three years through the option period.

“As we get through the option period and we start to collect more information and more data points, we’ll understand are those commitment numbers going up, or are they going down – and why exactly are they going up or down?” CES and other stakeholders can then respond accordingly to help make sure commitments are realised.

“It’s a long-term endeavour, the growth of the supply chain,” he explains. “Orders are some years away probably, so what we’re looking to establish is a credible and consistent way for that to be communicated straight from the projects…and for outcomes to be more visible.”

INTOG

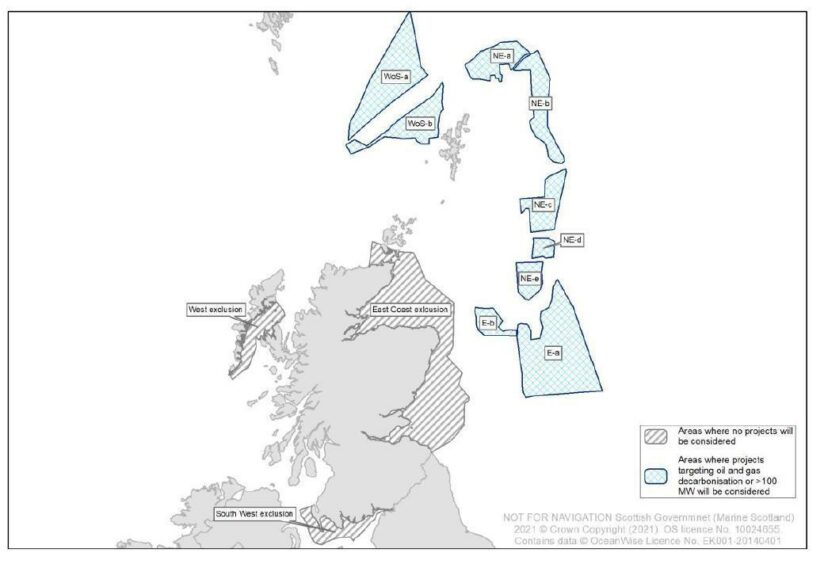

Were the ScotWind round not enough, CES is also now sifting through the 19 applicants for its Innovation and Targeted Oil and Gas (INTOG) offshore wind process.

The round will provide seabed space for both smaller floating ‘innovation’ projects up to 100MW and potentially larger, multi-GW developments that can be used to provide zero-carbon power for offshore assets.

Of the 19 applications, 10 relate to innovation bids, while nine have been submitted for the TOG element. CES is assessing applications with aim of offering exclusivity agreements for both IN and TOG projects by the end of April 2023.

Though Mr Maciver is necessarily tight-lipped as to the status of the bids, he says the response from regulators, industry groups and developers on the process has “all been very positive.”

Clearly each leasing process serves a slightly different purpose. “INTOG is more specifically on delivering innovation projects and seeing the benefit of that, whereas ScotWind is about commercial scale deployment, market opportunity and the ability of the offshore wind sector in Scotland to really industrialise itself,” he explains.

Included in that is the need for proportionality. ScotWind focused “very much on seabed area” resulting in bids for capacity exceeding expectations, and while there is no specific project cap TOG projects are limited to no more than five times the expected demand from their oil and gas consumers.

“We also have a maximum number of MW which can be leased in this round, so you will see those caps being implemented in accordance with the requirements of the plan,” Maciver says.

The opportunities are clear, though not all observers are bullish on developers’ prospects. Westwood Global Energy estimates that based on the number of oil and gas hubs ceasing production in the coming years and those unsuitable for electrification, only 14 hubs would be viable commercial opportunities in 2032 (19 in a high oil price scenario).

It also finds a potential conflict in the priorities of the North Sea Transition Authority (NSTA), which aims to reduce emissions, and those of CES which aims to maximise value from the seabed. “Bids are assessed on cost, not whether they are the best decarbonisation solution” the analysts add.

Instead, they said some developers had signalled a preference for “a more centralised and coordinated model” akin to Norway’s Trollvind scheme, rather than “a cutthroat auction” process reliant on competition.

Maciver acknowledged the claims but suggested “the commercials in the market around INTOG, TOG in particular, are much more unknown than was the position for ScotWind.”

“For us to look to manage the market in an environment where the landscape is as immature as it is might be misguided. It might show signals around expectations of option fee levels where the market wasn’t expecting to be and applicants might start following rather than leading.”

He also suggested the sizing of TOG schemes is likely to be variable depending on a multitude of factors around redundancy and offtake, but added “We do want to incentivize [developers] to find outlets and customers that deliver the scope 1 emissions reduction that NSTA and the NSTD is looking to achieve.”

“It’s in line with our objectives and I think having it different from ScotWind isn’t in some way contradictory. There’s quite sound logic to the approach.”

ScotWind 2

More widely, CES is keen to keep an open dialogue with other stakeholders to help ensure ScotWind and other energy schemes are delivered.

“There does seem to be a reflection to some extent of scale of the opportunity and the need for National Grid and the transmission operators to do something differently, and I think that’s a helpful thing,” he says.

“That’s also allowed a conversation to progress around alternative offtakers – so things like green hydrogen production has become, in my view, a very credible route to market for production projects.”

So, is the organisation ready to do it all again in the form of a much-discussed ScotWind 2?

Maciver says that all depends on Marine Scotland and the Scottish government, but that any movement would first require a marine planning framework for CES to follow.

“In order for them to do another planning process they would need medium-term policy coverage from Scottish Government, which indicates the aspirations beyond the early 2030s that would justify new areas of seabed needing to be made available.”

CES would also need to carry out more work to understand the scale and nature of market demand for new offshore wind rights.

“It’s an interesting mix of supply and demand that we would need to get comfortable with before we could start to progress new leasing,” he adds.

In any case – there is plenty more for CES to achieve in the meantime.

© PA

© PA © Supplied by Marine Scotland

© Supplied by Marine Scotland