When world-famous US firefighter Red Adair flew in from Houston to orchestrate the operation to “kill” the Piper Alpha wells, the mission appeared immense. Some even thought it impossible.

Jets of flame continued to blast from the devastated wellhead module, the only part of the platform to remain above the water.

The unit tilted at a precarious 45 degree angle and was a smoke-filled maze of sharp, twisted, oil-covered, blistering metal.

Many of the 36 wells on Piper Alpha had been shut by down-hole safety valves, but that was unknown to the team at the time.

The job for Adair – flanked by trusted lieutenants Raymond Henry and Brian Krause – was to work out how many remained open, and plug them.

The Piper Alpha assignment was something of a watershed moment for Adair, by then 73.

While aboard the helicopter flying him to the Tharos support vessel, the veteran had observed that getting to the wells would be a “bitch”, a biography by Philip Singerman records.

After an inspection of the smouldering module from the basket on Tharos’ cranes, the Texan, who revolutionised the science of capping exploding and burning wells, had to admit he was too old to go aboard the treacherous, slippery platform.

Mr Krause said having to stay back and direct the operation from the Tharos or its basket was very hard for his boss to take.

He would become “hyper” as wells frequently blew out and burned intensely for 20 minutes before dying down again.

Red Adair’s team worked 15 hours a day for weeks

Though confident the wellhead module wouldn’t collapse, the team kept a careful record of everything they uncovered so that if the module did give way and fall into the North Sea, divers would be able to use the records to continue the job.

It was a scenario no one wanted to unfold. A subsea well-kill could take two to three years to complete.

And so Adair’s team worked doggedly and methodically for 15 hours a day for three to four weeks, stopping only once, for three days, when the weather deteriorated to the point they could not battle on.

The top pair had a narrow escape when the P1 well caught fire just after they returned to Tharos.

The blowout caused the biggest blaze since the fatal explosion and would surely have killed them.

Despite Adair’s faith in his crew, a contingency plan was formulated in case they came up short.

A drill ship was sent to the field with the intention of drilling a relief well which would have channelled fuel away from well P1.

Gene Grogan, Occidental’s vice-president in charge of engineering, cautioned at the time that the operation did not have a “finite time scale” and the situation did not look “very good”.

Red Adair’s team seal the wells

But the team silenced their doubters.

They determined that valves on seven of the wells were not shut.

And their big break came when the wind blew in the right direction, giving Adair and his water cannon a clear shot of P1.

With the flames briefly controlled, his lieutenants swooped and stuffed a sealing device into the well before pumping fluid to the bottom of the pipe, killing the well.

The remaining wells were sealed permanently with cement within two weeks, leaving Adair to hold a triumphant press conference before returning home.

Away from the flames, Occidental’s marine department was responsible for recovering bodies, examining the platform jacket and identifying debris on the seabed from July 7 onwards.

With BP’s cooperation, Occidental was able to secure the use of the British Magnus vessel to carry out underwater surveys.

Bodies recovered

A series of sonar sweeps and excursions around the platform using remotely-operated vehicles were carried out.

Surveys were carried out in grids, which led to the recovery of 27 bodies from the seabed from July 10-29.

At the start of August, British Magnus was replaced by a dive support vessel, Seaway Condor, which in turn made way for two fishing vessels. They trawled for debris and human remains.

Most of the mangled wreckage was left in a huge underwater pile in the centre of what was left of the platform’s destroyed leg structure, or “jacket”.

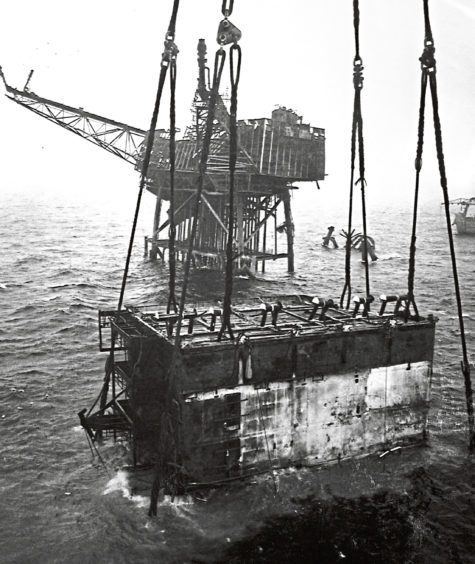

A total of 81 bodies were recovered from one of the accommodation modules, mainly after it was raised from the seabed and taken to Flotta in October 1988. The lifting operation required considerable equipment and manpower.

The wellheads module was toppled into the sea in an operation using explosives in March 1989.

Charges were used to cut the platform into two halves, or “towers”, before tugs pulled apart the sections, which fell to the seabed.

The operation took place following extensive studies and involved six vessels.

Authorities decided to decommission Piper Alpha in-situ because of concerns about the jacket collapsing during the next winter season – and the threat posed to vessels.

A detailed survey of the 100ft high pile of debris in the centre of the jacket was undertaken following toppling.

The structure and surrounding area are surveyed every five years and no concerns have been raised.

Red Adair: The world-famous firefighter

Red Adair was an American oil well firefighter who found worldwide fame for his daring and expertise in extinguishing and capping blowouts.

Born in Houston, Texas, he took up the trade after serving in a bomb disposal unit during the Second World War.

He founded Red Adair Co in 1959, and went on to battle more than 2,000 blazes.

In 1977, he and his crew were involved in capping the North Sea’s biggest oil well blowout at the Ekofisk Bravo platform in the Norwegian sector.

He returned in 1988 to help put out the fire on the Piper Alpha oil platform after the explosion claimed the lives of 167 men.

Still in action at the age of 75, he took part in extinguishing the oil well fires in Kuwait set by retreating Iraqi troops after the Gulf War in 1991.

Red Adair retired in 1993 and died in 2004, aged 89.

The 1968 John Wayne movie Hellfighters was based on his 1962 adventures in the Sahara Desert when he tackled a blaze nicknamed “the devil’s cigarette lighter”, which had burned at the Gassi Touil gas field for more than five months.

To follow more of our special Piper Alpha 30th anniversary coverage, click here.

Recommended for you